Latent fingerprints are one of the most important “invisible” forms of physical evidence in forensic work because they can link a person to an object or location even when no obvious mark is visible. A latent fingerprint is generally understood as a fingerprint left behind by natural skin secretions (and sometimes contaminants like blood, oils, or dust) that typically needs specialized methods to be seen and recorded. This blog explains what latent fingerprints are, why they form, how investigators find and develop them, and how the resulting prints are analyzed for identification.

What Makes a Latent Fingerprint?

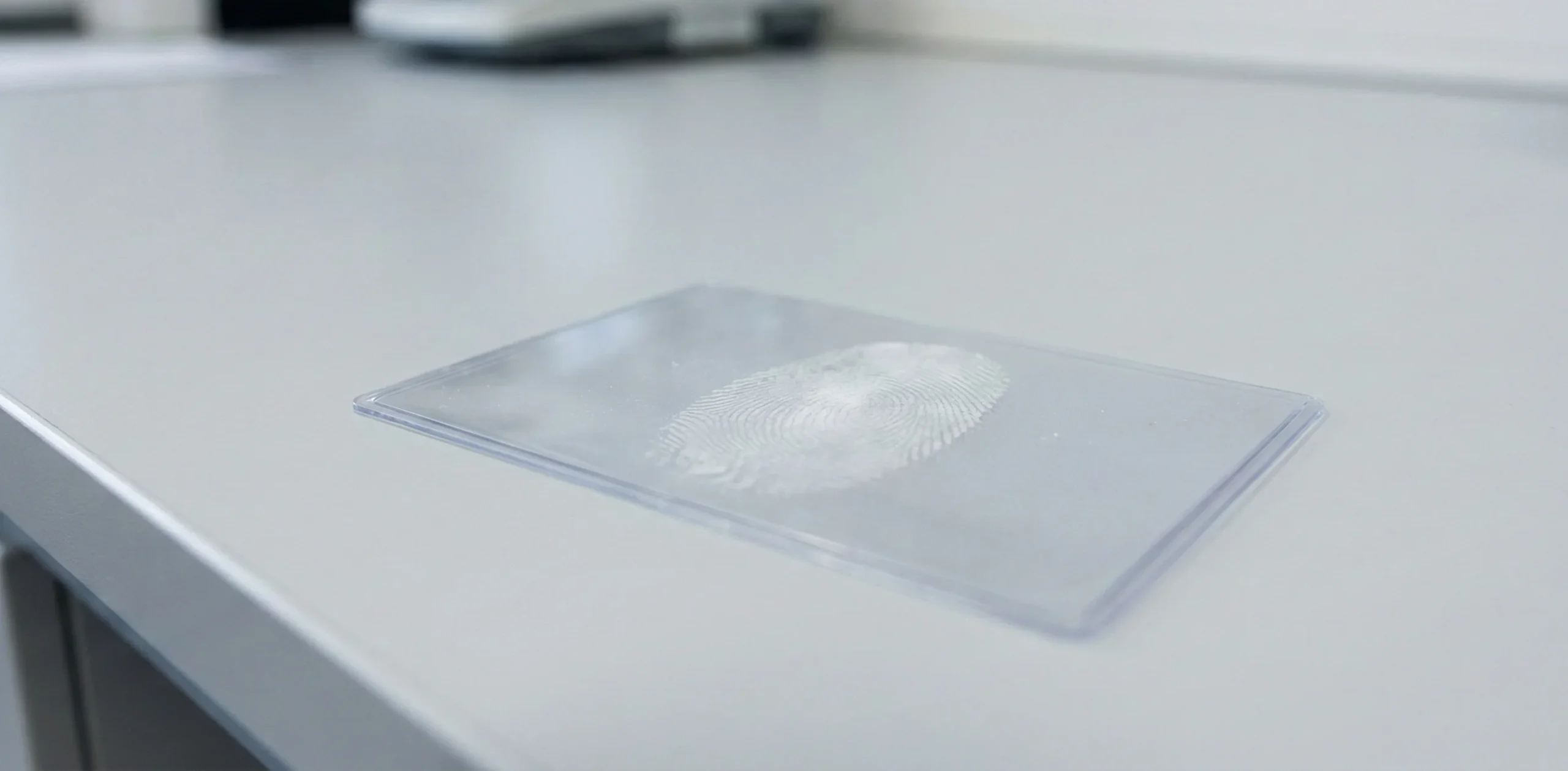

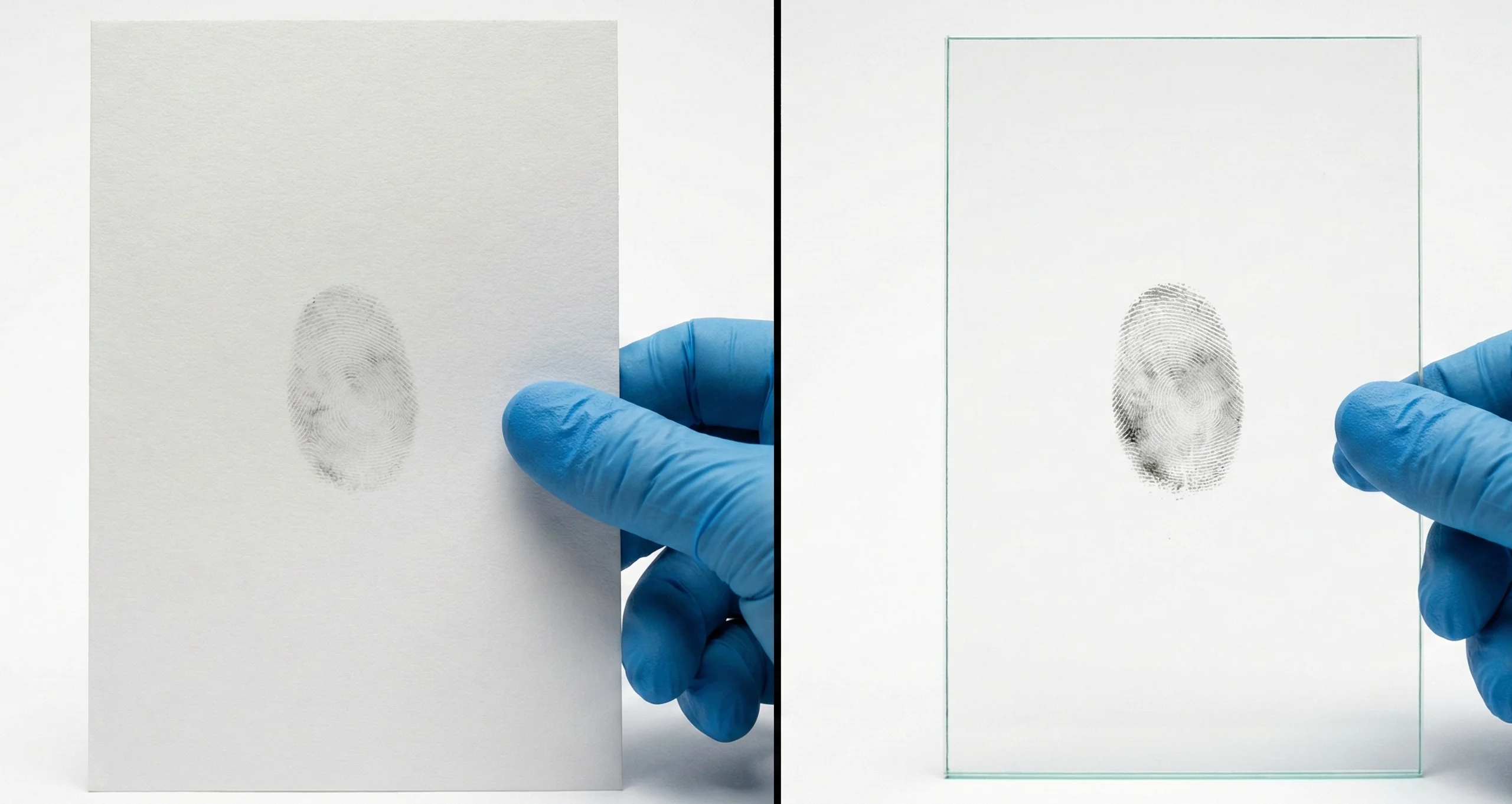

Latent fingerprints come from the unique friction ridge skin on fingers and palms, and they appear when ridge details transfer to a surface through natural secretions or contaminants. Because many of these deposits are colorless and thin, they often cannot be seen without enhancement techniques.

- Friction ridge anatomy: Ridges/valleys uniqueness (permanent post-birth).

Friction ridge skin consists of raised ridges and recessed furrows (valleys), forming patterns that can be used for human identification. The uniqueness and long-term persistence of these ridge formations are key reasons fingerprints are widely used in identification and forensic contexts. - Formation: Oils, amino acids, contaminants on surfaces (porous vs non-porous).

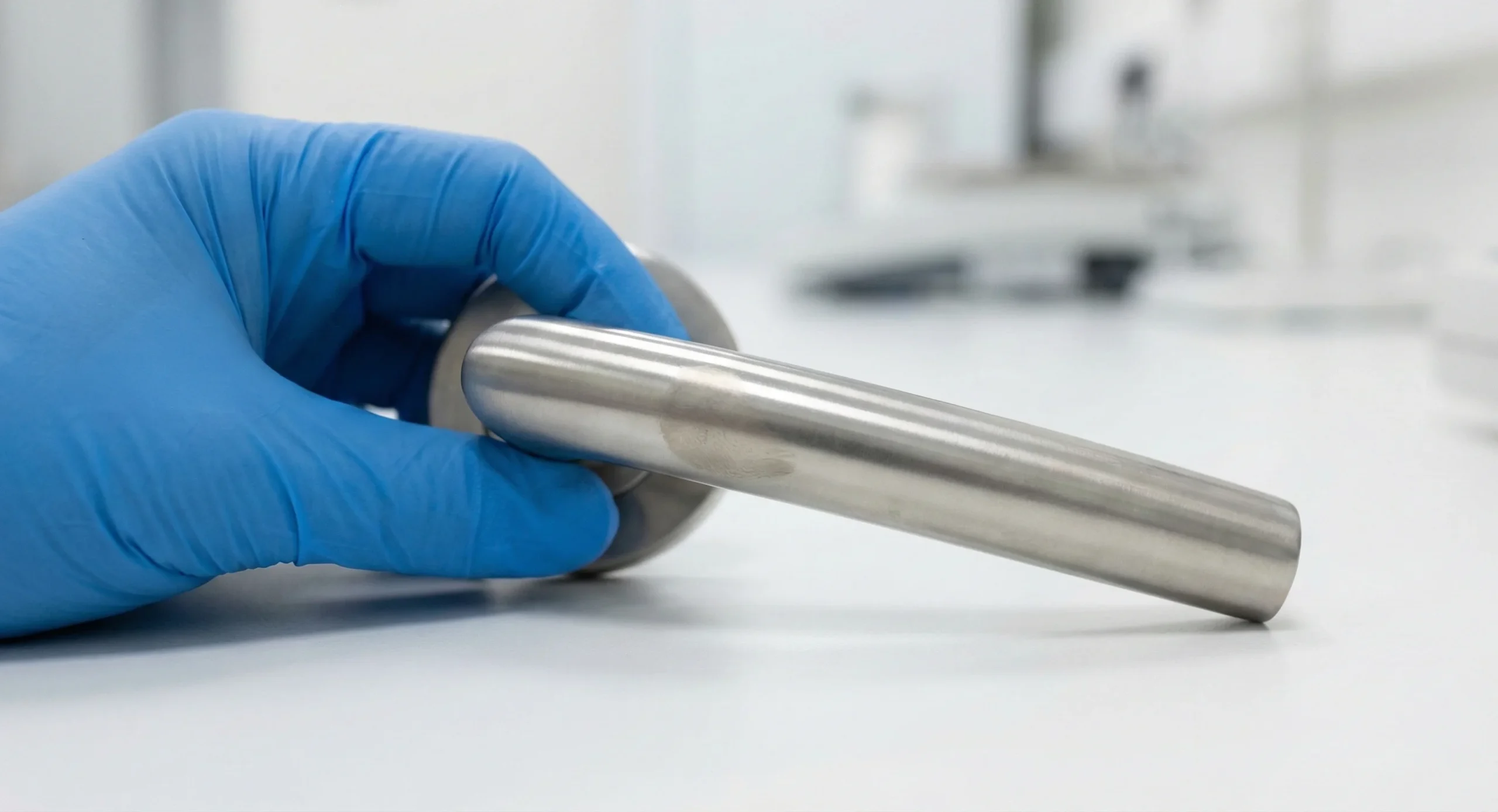

A latent fingerprint forms when finger contact transfers a residue that can include natural secretions and other materials present on the skin. The type of surface matters: non-porous surfaces (like glass or metal) tend to keep residues closer to the surface, while porous surfaces (like paper) can absorb components of the residue, influencing which development method works best. - Vs. patent/plastic prints: Why latents hide.

Latent prints are typically not immediately visible because the residue is thin and often colorless, unlike patent prints (visible because they are made in a colored substance) or plastic prints (visible 3D impressions in soft material). This difference is why latent prints usually require powders, chemicals, or specialized lighting to be detected and recorded.

Discovery at Crime Scenes

Finding latent prints begins with careful searching and scene handling, because touching or moving items can smear, remove, or contaminate fragile residues. Documentation and preservation steps are emphasized early because they affect whether prints can be successfully developed later.

- Surface ID: Handles, weapons, paper—avoid contamination.

Investigators first identify likely contact points—areas someone would naturally touch—then handle items in ways that reduce the risk of wiping away residue. This is a practical, methodical step: instead of treating every surface the same, examiners prioritize the most probable touch areas to preserve potential prints. - Preservation: Taping, photography, sketches before touch.

The outline’s preservation focus reflects standard forensic logic: record what is present before processing changes the surface. Photographs and notes help maintain a record of where prints were located and what condition the evidence was in before development steps potentially alter it.

Development Techniques

Latent print development is the process of making an invisible print visible enough to document and compare, and it typically uses physical, chemical, optical, and digital techniques chosen for the surface and residue condition. Selection matters because different techniques interact with different components of fingerprint residue, and some methods work best on non-porous items while others are designed for porous substrates.

- Physical: Powder dusting (smooth surfaces), alternate light sources.

Powder dusting is described as a long-used method in which fine powders adhere to moisture and oils in fingerprint residues, helping ridge patterns become visible on smooth, non-porous surfaces. The outline’s mention of alternate light sources aligns with the use of contrasting/fluorescent approaches to make developed prints easier to see and photograph under specific lighting. - Chemical: Cyanoacrylate fuming (non-porous), ninhydrin/DFO (porous), dyes (Rhodamine 6G).

Cyanoacrylate (super glue) fuming is described as effective on non-porous surfaces because it reacts with latent print residues and creates a visible deposit that can make prints more durable for further processing. For porous surfaces such as paper, chemical reagents are described as essential because they react with components of the residue embedded in the substrate. The outline’s dye examples (including Rhodamine 6G) match the idea of post-treatment dye staining to increase contrast and visibility—especially when fluorescence under specific wavelengths helps separate ridge detail from background patterns. - Digital: Scanning/enhancement software.

Digital imaging is described as a non-destructive way to improve the visibility of ridge detail by adjusting factors like contrast, brightness, and color after a print has been captured. This helps examiners interpret prints that are faint or partially developed, while preserving the original evidence state for review and re-analysis.

| Method | Best surfaces | What it does | Common use case |

| Powder dusting | Smooth, non-porous surfaces | Fine powder adheres to moisture/oils in residue, revealing ridge detail. | Quick visualization on items like glass/metal where residue sits on the surface. |

| Cyanoacrylate (super glue) fuming | Non-porous surfaces | Reacts with latent residues and forms a visible deposit that can be further processed. | Developing prints on plastics and other non-porous evidence for durable ridge detail. |

| Chemical reagents for porous items (e.g., ninhydrin/DFO as named in outline) | Porous surfaces (paper/cardboard/untreated wood) | Chemical reactions target components in residue absorbed into porous substrates. | Revealing prints on documents and packaging where residue penetrates the material. |

| Dye staining (e.g., Rhodamine 6G as named in outline) | Typically after earlier development steps | Fluorescent dyes bind to developed residue and enhance contrast under appropriate light. | Improving visibility when background patterns or low contrast obscure ridge detail. |

| Digital enhancement | Captured print images (after photography/scanning) | Software-based adjustment of contrast/brightness/color to clarify detail. | Assisting interpretation of faint/partial prints without altering physical evidence. |

Analysis and Matching

After a latent print is developed and documented, the next step is analysis and comparison, focusing on ridge detail and specific features used to determine whether two prints come from the same source. The outline emphasizes minutiae and a combination of automated and expert-driven work, reflecting the common practice of using systems to support searching while relying on examiners for interpretation.

- Minutiae exam: Endings, bifurcations (12+ points for ID).

Minutiae are the small ridge features examiners look for, such as ridge endings and bifurcations, and they are described as central to fingerprint analysis because they provide distinctive detail beyond overall pattern type. The blog source provided does not establish a universal “12+ points” identification threshold, so this post treats minutiae as the focus of comparison without asserting a fixed minimum number required for identification. - AFIS automation + manual verification; evidentiary standards (FBI guidelines).

The outline’s “automated + manual” framing matches how modern workflows often combine automated searching with human examination to assess the quality and meaning of potential matches. The attached source references institutions like the FBI and the “Fingerprint Sourcebook” in the context of best practices and knowledge development, but it does not provide specific courtroom standards or a definitive rule set; therefore, the blog notes the institutional role without claiming detailed “FBI guidelines” beyond that general attribution.

Challenges and Advances

Latent fingerprint work faces practical challenges because residues degrade, surfaces vary, and environments can reduce print quality, yet new research aims to improve detection and reliability. The outline also flags that advances raise legal and ethical questions, especially around reliability and responsible use.

- Limits: Age, environment; future: Nanomaterials, AI matching.

The attached source explicitly highlights that environmental influences and print condition affect technique choice and results, which implies real-world limits such as degradation and variability in residue/surface interactions. The same source points to emerging technologies and ongoing innovation as future directions, but it does not provide detailed, verifiable claims about nanomaterials or AI performance; accordingly, this post only states that innovation is an active area without making specific efficacy claims. - Ethics: Error rates, courtroom reliability.

The attached source notes that advances in latent fingerprint technology raise ethical and legal considerations, reinforcing that reliability and responsible use are part of modern forensic discussions. Because the provided materials do not quantify error rates or specify courtroom admissibility criteria, this section avoids numeric claims and focuses on the general need for careful, defensible practice when using fingerprint evidence.

Conclusion

Latent fingerprints turn ordinary touch into potential evidence, but their value depends on careful discovery, correct development choices, and disciplined analysis. Understanding how these prints form and why different surfaces require different visualization methods helps explain why latent print work blends chemistry, documentation, imaging, and expert interpretation. As techniques continue to evolve, the core goal remains the same: make invisible ridge detail visible and usable in a way that is accurate and responsibly applied.