Anti-Money Laundering (AML) in banking refers to a framework of laws, regulations, and internal controls designed to prevent criminals from introducing illicit funds into the legitimate financial system. Money laundering enables activities such as drug trafficking, corruption, fraud, and terrorism financing, all of which can destabilize economies and undermine public trust in financial institutions.

In banking, AML is not just about avoiding fines; it is a core component of risk management and ethical operations that protects both the institution and the wider financial system. Banks implement AML measures to detect suspicious activities, report them to authorities, and block attempts to legitimize “dirty money,” thereby acting as a crucial line of defense against financial crime.

Key ideas:

- AML is a set of laws, regulations, and controls designed to stop illegal funds entering the financial system.

- Banks act as gatekeepers, identifying and reporting suspicious activity.

- Effective AML supports financial stability, ethics, and customer trust.

Understanding Money Laundering

Money laundering is the process of disguising the origins of illegally obtained funds so that they appear to come from legitimate sources. Criminals use banks and other financial channels to integrate illicit proceeds into the formal economy, making it harder for law enforcement to trace and confiscate the funds.

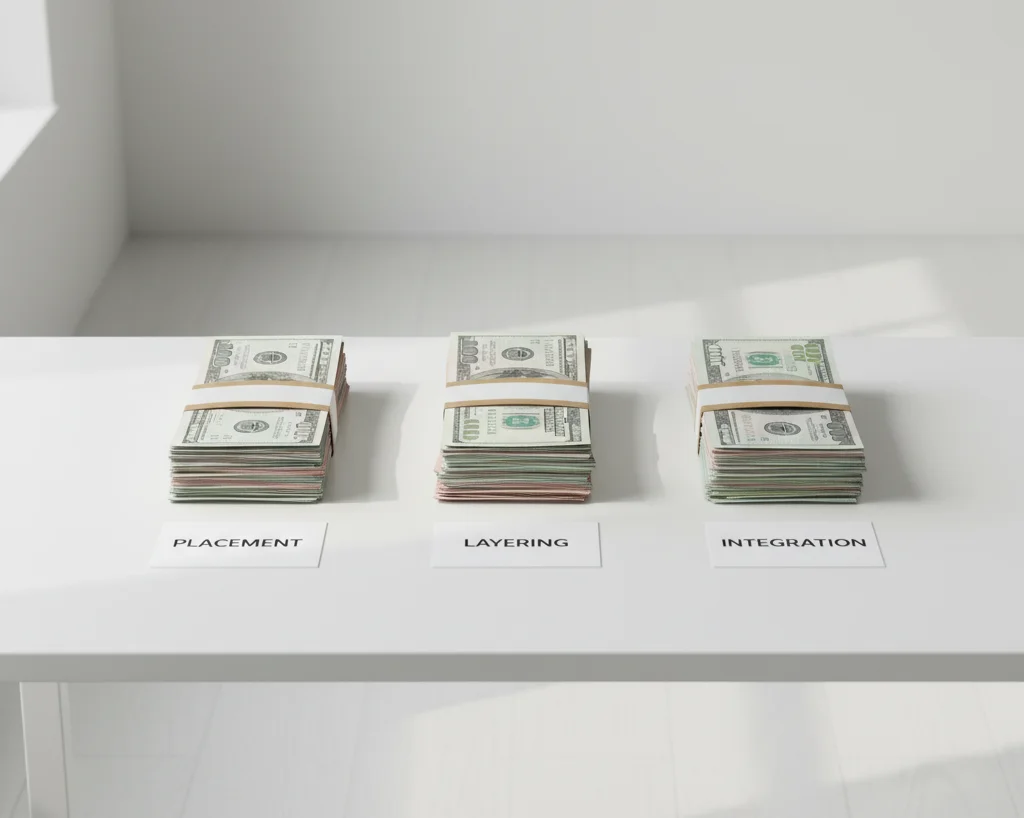

The money laundering process is commonly described in three stages:

- Placement

- Illicit cash is first introduced into the financial system.

- Examples: cash deposits into bank accounts, purchasing cashier’s checks or money orders, using cash‑intensive businesses as a front.

- Layering

- Multiple or complex transactions are carried out to obscure the origin and ownership of the funds.

- Examples: frequent wire transfers, moving funds through multiple accounts or jurisdictions, trading in financial instruments, using shell companies.

- Integration

- Laundered funds re‑enter the economy as apparently legitimate assets.

- Examples: investments, real estate purchases, business ventures, luxury goods.

Banks are attractive targets for money launderers because they:

- Handle large volumes of domestic and cross‑border transactions.

- Offer diverse financial products and services that can be misused.

- Provide access to the global financial system through correspondent relationships.

Common laundering tactics in banking can include:

- Structuring (breaking up deposits to stay below reporting thresholds).

- Using third‑party or mule accounts.

- Rapid movement of funds between accounts, institutions, or countries.

Regulatory Framework for AML in Banking

AML in banking is shaped by a combination of international standards and national laws, supported by regulatory and supervisory guidance. Together, these define what banks must do to prevent, detect, and report money laundering and terrorist financing.

At the international level:

- The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) sets global AML/CFT (Counter‑Terrorist Financing) standards.

- FATF Recommendations cover areas such as customer due diligence, beneficial ownership transparency, sanctions, and suspicious transaction reporting.

- Countries are regularly assessed on how effectively they implement these standards.

At the national or regional level:

- Governments transpose FATF standards into laws and regulations.

- Examples (by type, not by exact statute text):

- Banking secrecy and reporting laws that require record‑keeping and filing of specific reports.

- AML acts and regulations that define program, risk assessment, and control requirements for banks.

- Regional directives (e.g., in the EU) that harmonize AML rules across member states.

Supervisory and enforcement bodies:

- Oversee how banks implement AML requirements.

- Conduct examinations and thematic reviews.

- Impose penalties, remediation plans, or business restrictions for non‑compliance.

Consequences of non‑compliance can include:

- Heavy monetary fines (often in the hundreds of millions or billions for major failures).

- Restrictions on business activities, such as limits on opening new accounts or operating in certain markets.

- Loss of licenses, enforcement actions against individuals, and lasting reputational damage.

Core Components of AML Programs in Banks

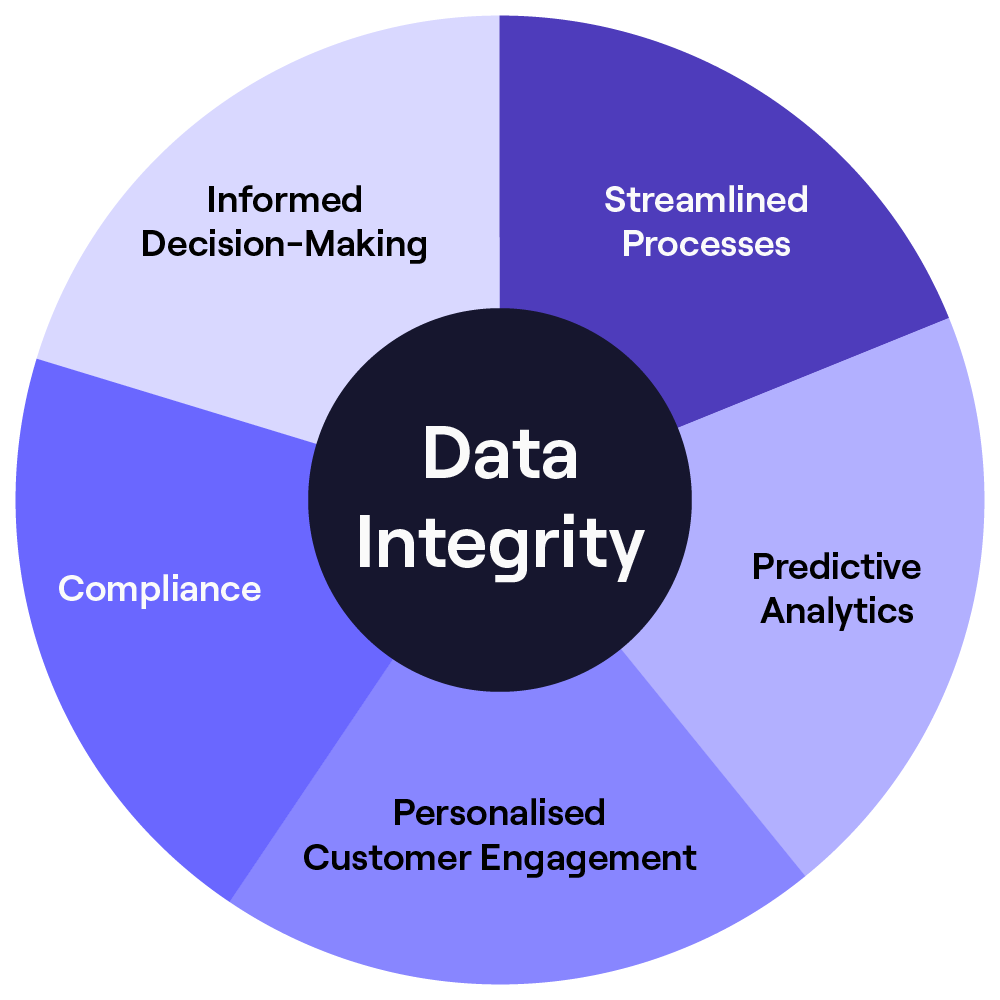

AML programs in banks are built around several core components that work together to identify, assess, and mitigate money laundering and terrorist financing risks. A sound program is risk‑based, documented, and embedded into day‑to‑day operations.

Customer Due Diligence (CDD) and Know Your Customer (KYC)

Banks must understand who their customers are, what they do, and what risk they pose.

Key elements:

- Identity verification

- Collecting and verifying customer identification information (e.g., government ID, business registration, beneficial ownership details).

- Customer profiling and risk rating

- Understanding the nature and purpose of the relationship (e.g., personal banking vs. corporate account; low‑risk retail vs. high‑risk industries).

- Assigning risk levels (low, medium, high) based on factors like geography, product type, and customer type.

- Enhanced Due Diligence (EDD)

- Applying deeper checks for higher‑risk customers, such as politically exposed persons (PEPs), complex corporate structures, or customers in high‑risk jurisdictions.

Transaction Monitoring and Suspicious Activity Reporting

Once customers are onboarded, banks must monitor their activity and escalate concerns.

Core aspects:

- Automated transaction monitoring systems

- Use rules and scenarios to flag unusual or inconsistent behavior (e.g., sudden large transfers, frequent cross‑border payments, unusual cash activity).

- Alert review and investigation

- Compliance analysts review alerts, request additional information where needed, and document decisions.

- Suspicious Activity/Transaction Reports (SAR/STR)

- When activity cannot be reasonably explained, the bank files a report with the relevant authority.

- Reports typically include details of the customer, accounts, activity, and rationale for suspicion.

Also Check: What Is Social Engineering? A Complete Definition and Explanation

Risk‑Based Approach to AML

Modern AML expectations are explicitly risk‑based rather than purely rules‑based.

This means:

- Banks must conduct an enterprise‑wide risk assessment covering:

- Products and services (e.g., private banking, trade finance, remittances).

- Customer types (retail, SME, large corporates, financial institutions).

- Delivery channels (online, branches, intermediaries).

- Geographies (domestic, foreign, high‑risk jurisdictions).

- Controls should be proportionate to risk, for example:

- More intensive monitoring for cross‑border or high‑risk industry clients.

- Simpler controls for low‑risk, basic retail products.

- The risk assessment should be reviewed periodically and updated as the business or threat landscape changes.

Record‑Keeping and Reporting Obligations

Robust record‑keeping is critical for audits, regulatory reviews, and law‑enforcement investigations.

Typical obligations:

- Maintaining customer identification and due diligence records for a minimum number of years after the relationship ends.

- Retaining transaction records (amount, date, counterparties, purpose) for a defined period.

- Being able to provide information promptly to regulators or law‑enforcement agencies upon request.

In addition to suspicious reports, banks may be required to submit:

- Threshold reports (e.g., large cash transaction reports).

- Cross‑border transaction reports.

- Periodic regulatory returns on AML program metrics and governance.

Role of Technology in Enhancing AML

Technology has become essential for banks to manage AML obligations at scale and keep pace with increasingly sophisticated financial crime.

Biometrics for Identification and Authentication

Biometric technologies provide strong, unique links between individuals and their accounts.

Common biometric methods:

- Fingerprint recognition.

- Facial recognition.

- Iris or palm vein recognition, depending on use case.

How biometrics support AML:

- Strengthen the reliability of KYC during onboarding by ensuring that the person is who they claim to be.

- Reduce risks of identity theft, impersonation, and synthetic identities.

- Support secure, ongoing authentication for account logins, high‑risk transactions, or remote services.

AI, Machine Learning, and Advanced Analytics

Banks increasingly use AI and machine learning models to enhance detection capabilities.

Benefits:

- Analyze very large volumes of transactions and customer data quickly.

- Identify complex or subtle patterns that rules‑based systems might miss, such as networked behavior across multiple accounts.

- Reduce false positives by better distinguishing between normal and anomalous behavior.

Typical use cases:

- Behavioral profiling based on peer groups (comparing a customer’s behavior to similar customers).

- Network analysis to detect links among entities, accounts, and transactions.

- Prioritization of alerts based on risk scores.

Automation and Operational Efficiency

Automation complements analytics by streamlining routine compliance tasks.

Examples:

- Automated screening against sanctions, PEP, and adverse‑media lists.

- Workflow tools for case management, investigations, and reporting.

- Automated report generation and data aggregation for regulators and internal governance.

Benefits for banks:

- Lower operational costs by reducing manual, repetitive work.

- Fewer human errors and more consistent application of policies.

- Faster response times for investigations and regulatory requests.

Challenges and Best Practices in AML Implementation

Even with technology and clear rules, implementing effective AML programs is challenging.

Key Challenges

- Evolving regulations

- Frequent updates to laws, regulations, and guidance across different jurisdictions.

- Need to harmonize global and local requirements for multinational banks.

- Adaptive criminal tactics

- Criminals exploit new products (e.g., real‑time payments, digital assets) and complex structures.

- Constant innovation in hiding beneficial ownership and transaction trails.

- Data and system fragmentation

- Customer and transaction data often reside in multiple legacy systems.

- Difficulties in building a single customer view across business lines and geographies.

- High alert volumes and false positives

- Traditional rules can generate many alerts that turn out to be benign.

- Strains compliance teams and increases investigation backlogs.

- Talent and expertise constraints

- Shortage of skilled AML analysts, investigators, model risk experts, and regulatory specialists.

Best Practices

Successful AML programs typically include:

- Strong compliance culture and governance

- Clear “tone from the top” emphasizing integrity over short‑term gains.

- Board and senior management oversight of AML risk, reporting, and resourcing.

- Regular and targeted training

- Training for front‑line staff on red flags and onboarding rules.

- Specialized training for compliance, operations, and senior leaders.

- Refreshers when regulations or internal policies change.

- Genuinely risk‑based approach

- Using risk assessments to drive priorities, controls, and resource allocation.

- Periodic updates as products, markets, or threat patterns evolve.

- Use of modern technology and data

- Adoption of advanced analytics, case‑management tools, and high‑quality data sources.

- Ongoing validation and tuning of models and scenarios.

- Independent testing and continuous improvement

- Internal audit and external reviews to identify gaps.

- Structured remediation plans and follow‑up tracking.

Impact of AML on Banking Industry and Global Economy

AML has implications far beyond individual banks. Effective programs contribute to the soundness of the overall financial system and global security.

Safeguarding Financial System Integrity

AML measures:

- Help prevent large flows of illicit funds from distorting markets or asset prices.

- Reduce the risk that banks are used as conduits for systemic criminal activity.

- Support confidence among depositors, investors, and counterparties.

Weak AML controls, by contrast, can:

- Lead to concentration of criminal funds in specific institutions or jurisdictions.

- Trigger loss of correspondent banking relationships and financial exclusion in some regions.

- Damage a country’s reputation and invite enhanced scrutiny from international bodies.

Combating Terrorism Financing and Organized Crime

Because many of the tools used for AML also apply to terrorist financing and organized crime, strong AML frameworks:

- Help disrupt financial flows to terrorist groups and criminal networks.

- Provide law enforcement with transaction data and intelligence from suspicious activity reports.

- Support international cooperation in investigations and asset‑recovery efforts.

Protecting Reputation and Customer Trust

For banks, robust AML programs:

- Demonstrate commitment to ethical conduct and regulatory compliance.

- Reduce the likelihood of high‑profile scandals and costly enforcement actions.

- Support long‑term relationships with customers, investors, and correspondent banks.

Conversely, repeated AML failures can result in:

- Loss of customer confidence and market value.

- Business restrictions, license threats, or forced exits from certain markets.

Conclusion

Anti-Money Laundering (AML) in banking is a foundational pillar of financial integrity, combining laws, regulations, governance, and technology to prevent criminals from turning illicit proceeds into legitimate assets. By understanding how money laundering works and implementing robust, risk‑based AML programs, banks can better detect and deter financial crime.

Effective AML efforts:

- Protect individual institutions from financial, legal, and reputational damage.

- Safeguard the broader financial system and global economy from destabilizing criminal flows.

- Support the fight against terrorism financing and organized crime while preserving customer trust.