The human eye has long been described as a “window” into both identity and health, and retina scanning turns this idea into a powerful security tool. By focusing on internal blood vessel patterns rather than external features, retina scans provide a biometric signature that is difficult to forge and highly stable over time. This makes the technology especially attractive in contexts where even small security gaps can have serious consequences, such as defense, critical infrastructure, and certain financial operations.

How Retina Scanning Works

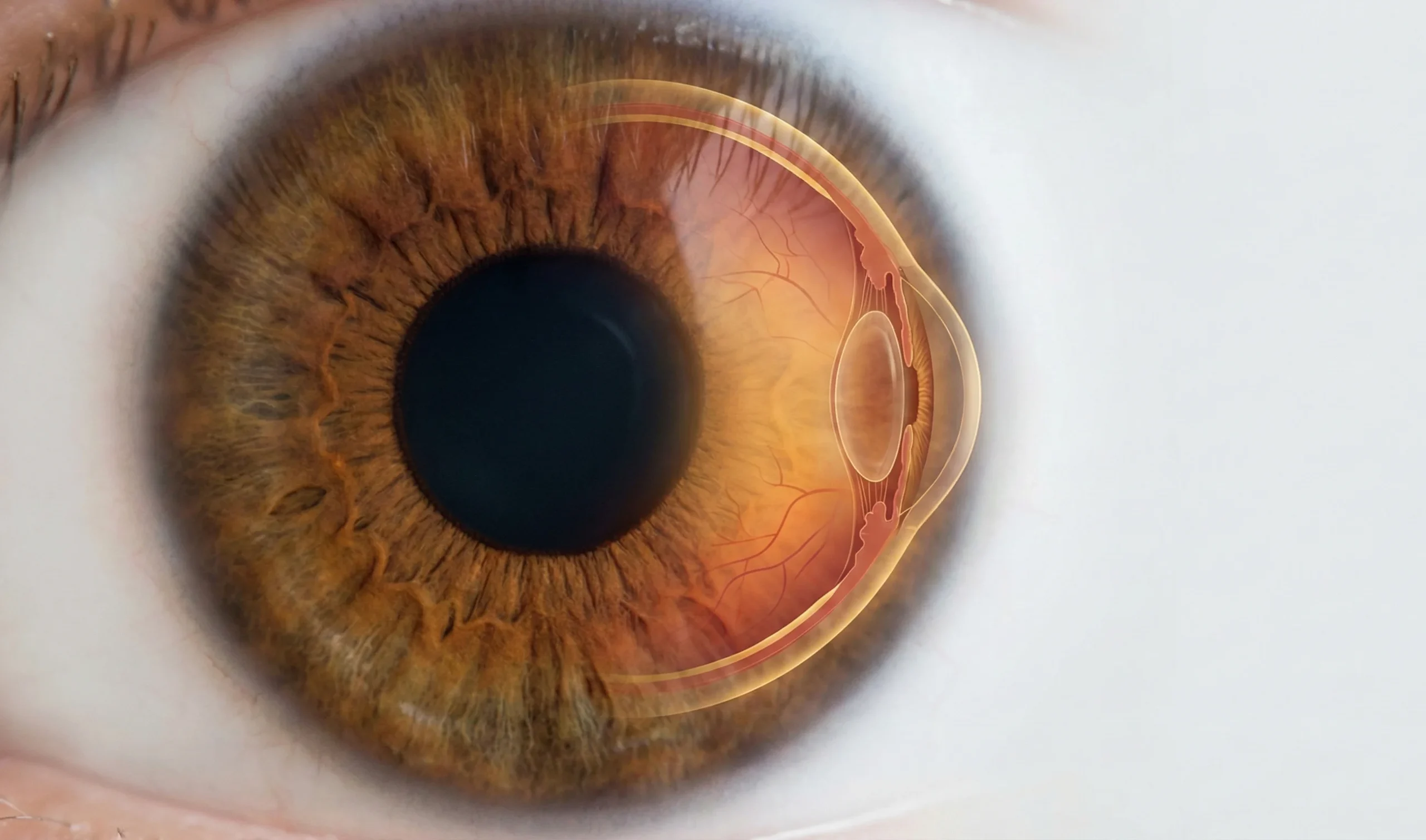

Retina scanning technology starts by directing a low-intensity infrared beam through the pupil to illuminate the retina, which is the light-sensitive tissue lining the back of the eye. The blood vessels in the retina absorb light differently from surrounding tissue, creating a high-contrast “map” that the scanner captures as an image.

Once this image is captured, specialized software extracts the pattern of vessels and converts it into a mathematical template that can be stored in a secure database. During later authentication attempts, a new scan is performed and the resulting template is compared to the stored reference, with matching thresholds set to minimize false accept and false reject rates. Because the vascular structure of the retina is highly unique and changes very little over a person’s lifetime, this process can achieve very high accuracy when the system is properly calibrated and maintained.

Retina vs. Iris Scanning

Retina and iris scanning are often discussed together because both rely on the eye, but they target different anatomical regions and use different capture methods. Retina scanning analyzes the blood vessel pattern on the inner surface at the back of the eye, requiring the scanner to look through the pupil and capture data at close range. In contrast, iris recognition focuses on the colored ring around the pupil, using cameras to image distinctive textures on the iris surface from a comfortable distance.

These differences lead to distinct trade-offs. Iris systems typically support quicker, more convenient user experiences and can work at arm’s length or even farther, which makes them better suited for high-throughput settings like airports or access gates. Retina systems generally require the user to align their eye closely with the device and maintain focus on a fixed target, but in return they offer extremely detailed internal patterns that are harder to replicate or spoof. Medical conditions can influence both modalities, but vascular issues such as severe diabetic retinopathy are more likely to affect the retina than the iris, potentially impacting scan quality and reliability in those cases.

Advantages of Retina Scanning

Retina scanning offers several advantages that explain its strong position in high-security biometrics.

- Extremely high distinctiveness: The vascular pattern of each retina is highly complex, and the probability of two individuals sharing the same pattern is extremely low, supporting very accurate identification at scale.

- Long-term stability: In the absence of serious disease, retinal blood vessel patterns remain largely stable throughout adult life, reducing the need for frequent re-enrollment and helping maintain consistent performance.

- Resistance to simple spoofing: Because retina imaging involves internal structures rather than surface features, it is much harder to counterfeit with basic photos or masks compared with some other biometric traits.

- Potential health insight: The same retinal images used for identification can reveal signs of vascular or metabolic conditions, giving the technology a secondary value when integrated into appropriate healthcare workflows.

These benefits explain why retina scanning is often discussed for environments where security and identity assurance are considered non-negotiable, rather than for casual consumer use.

Disadvantages and Challenges

Despite its strengths, retina scanning faces practical and perception-related challenges that limit its widespread deployment.

- User comfort and intrusiveness: The need to place the eye very close to the scanner and maintain a fixed gaze can feel invasive or uncomfortable for some users, especially in repeated or high-volume scenarios.

- Equipment cost and complexity: Retina scanners require specialized optics, controlled illumination, and precise alignment, which tend to make them more expensive and complex to deploy than many iris or facial recognition systems.

- Sensitivity to health conditions: Eye diseases that affect retinal vessels, such as advanced diabetic retinopathy or certain vascular disorders, can degrade image quality and reduce system accuracy, making inclusive deployment more challenging.

- Privacy and data protection concerns: Like other biometrics, retinal templates must be carefully secured, because they represent permanent traits that cannot be changed if compromised; this raises questions about governance, storage, and long-term risk.

These limitations explain why many organizations opt for other modalities in everyday access control, using retina scanning only where its incremental security value outweighs deployment and usability hurdles.

Real-World Applications

Retina scanning is already in use, but primarily in specialized, high-security, or high-stakes environments rather than mass-market scenarios.

- Government and defense: Certain agencies and installations use retina scanners to control access to restricted zones, taking advantage of the modality’s accuracy and resistance to casual spoofing.

- Critical infrastructure and research: Facilities such as laboratories, nuclear sites, and research centers may deploy retina scanning where unauthorized entry could lead to safety, economic, or intellectual property risks.

- Humanitarian and programmatic use: Some identity and aid programs have explored retinal or similar ocular biometrics to authenticate individuals reliably without relying solely on physical documents, particularly in complex field environments.

- Healthcare and health-linked identity: Healthcare organizations can combine secure access with clinical value by leveraging retinal imagery to both verify identity and support ophthalmic or systemic health assessments, provided appropriate clinical systems are in place.

- Specialized financial and enterprise systems: A limited number of financial and enterprise setups have evaluated or piloted retina scanning for high-risk transactions or administrative access, where very strong authentication is required.

In many of these cases, retina scanning sits alongside other biometrics and security measures, forming part of a layered defense strategy rather than acting as the only control.

Conclusion

Retina scanning stands at the intersection of cutting-edge security and advanced imaging of one of the body’s most intricate structures. Its ability to capture highly unique and stable vascular patterns gives it a level of precision that few other biometric modalities can match, making it especially valuable in environments where security failures are unacceptable. At the same time, its intrusive capture process, higher equipment costs, and sensitivity to certain health conditions mean it is unlikely to replace more convenient biometrics in everyday consumer applications in the near term. As hardware, algorithms, and privacy safeguards continue to improve, retina scans are poised to remain a specialized but powerful option—helping organizations build layered, resilient biometric security that looks beyond the iris to the very back of the eye.